AERIAL INSECTIVORE ROOSTS

“Fall is a season of drama in the tree swallows' yearly cycle. A single idea, or an urge, seems to grip every swallow in the land. The nesting season with its quarrels over, the swallows draw together with a common interest in preparation for their next step, the long migration they will take in companies of hundreds or thousands. In August and September we see them gathering in the great marshes by the sea, where they linger for many days in ever-increasing numbers, young and old…”

- Arthur Cleveland Bent

Every autumn morning in North America, millions of Purple Martin and Tree Swallows emerge from their roosts in wetlands, forests, bridges, and even urban centers. These roost emergence’s are so large that they appear on weather radar as “roost rings”, originally dubbed “angels” by the first radar technicians that observed the rings. Not only are these roosts fascinating to watch (both on radar imagery and in-person), but they are critical stopover locations for entire populations of these declining species, and can be studied on a large scale, thanks to weather radar data.

I grew up in Old Lyme, Connecticut, home of one of the biggest and oldest known Tree Swallow roosts, which settles in a small phragmites island on the Connecticut River. I would swim out to the middle of the river and watch as the swarms of swallows would dance around me, grabbing sips of water before forming into an immense cloud that funnels into the island like a tornado touching down.

My time with the Old Lyme roost has inspired me to perform both undergraduate and graduate work studying these roosts; from assessing how wind affects roost sizes (see DOI link below), measuring effects of anthropogenic disturbance on roost size/persistence (in progress), and detecting roost communities with network analysis, to assess the effects of population declines on roost network connectivity (in progress).

MAPS BANDING EFFORT

“Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language.”

- Aldo Leopold

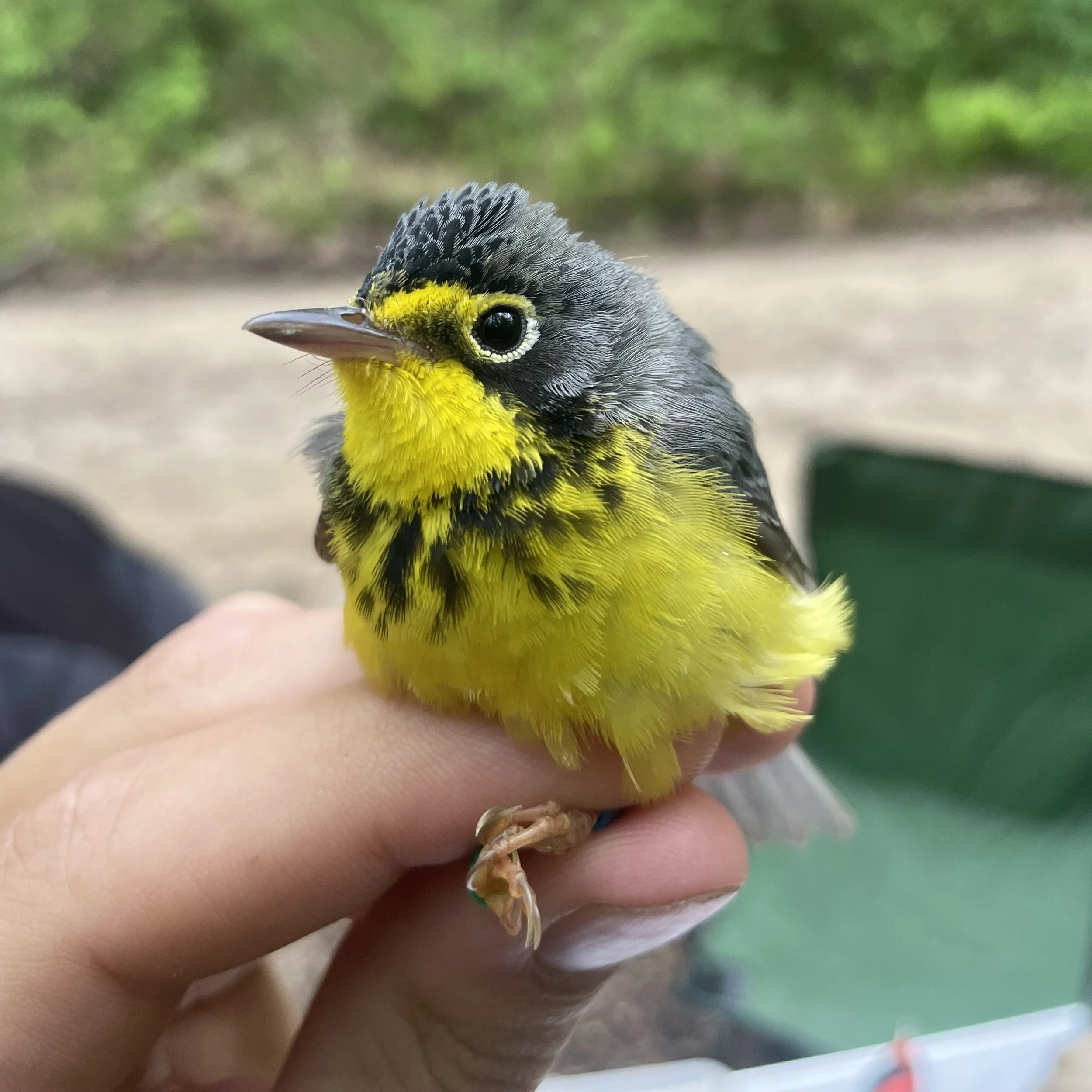

From spending many years in the field as a technician, I always wondered if climate change was not only impacting the survival of wildlife, but also our ability to study wildlife. With that in mind, I began a project that is evaluating the impact of adverse weather events on banding productivity, using a 30-year dataset provided by the Mapping Avian Productivity and Survivorship program. The project aims to assess the impact of weather on overall banding efficiency, determine which bird conservation regions are more vulnerable to adverse weather conditions (rain, high winds, and high temperatures), and determine if adverse weather conditions have increasingly affected banding efforts over the history of the MAPS program.

FUTURE WORK

“Life has unfathomable secrets. Human knowledge will be erased from the archives of the world before we possess the last word that the Gnat has to say to us.”

- Maurice Maeterlinck

Ultimately, I find inspiration in uncovering the intricacies of nature. Studying ecology is like studying the connections within a giant, tangled, interconnected web. Whenever I ponder a potential research project, I always inevitably take one, two, three steps back to see the bigger picture; how the subject of focus fits into the web of life. I’ve also grown to appreciate how species and individuals within ecosystems can be studied not just by their characteristics, but their relationships. How these relationships adapt in response to environmental or demographic changes fascinates me. With that in mind, I am strongly interested in applying complex systems science to answer large-scale questions and fundamental theory, all with the intention of better protecting the natural world.